Over at the IQSS Social Science Statistics blog, Richard Nielsen had a great post on pre-registration (link). He writes,

In response to a comment by Chris Blattman, the Givewell blog has a nice post with “customer feedback” for the social sciences. Number one on the wish-list is pre-registration of studies to fight publication bias — something along the lines of the NIH registry for clinical trials. I couldn’t agree more. I especially like that Givewell’s recommendations go beyond the usual call for RCT registration to suggest that we should also be registering observational studies.

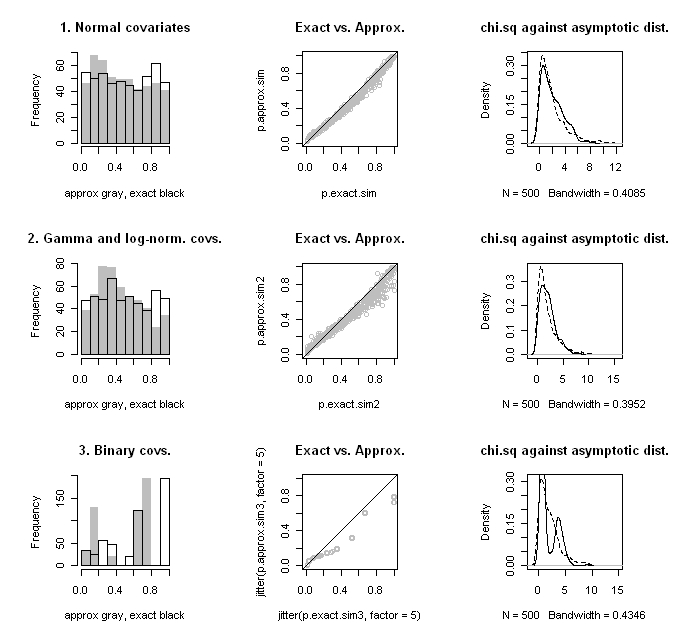

As Richard notes, much of the interest in pre-registration is to reduce the publication bias that most certainly afflicts us (evidence from Gerber and Malhotra here). As a result, like in medicine, most published research findings are probably false (link). Some more arguments in favor of pre-registration to control publication bias for both clinical trials and observational studies are given by Neuroskeptic (link).

What I want to propose that the pre-registration, and the “ex ante science” ideal on which it is based, is great for positive theorists, especially for those who want to do mostly or even only positive theory. How so? For two reasons. First, theory and substantive insights are what editorial boards would need to judge the quality and relevance of research questions and hypotheses. Second, ex ante science provides a steadier stream of puzzles that theorists can delight in trying to work out.

A central role in publication decision processes

Obviously, the quality and relevance of hypotheses ought to be taken into account in judging whether a submission is publication worthy. For a causal or descriptive analysis, identification alone is insufficient to make a study worth one’s time. We want to know if the questions being asked are important and whether the hypotheses are coherent. Consider a journal publication decision mechanism that applies the logic of ex ante science. A proposed submission comes in with hypotheses and research design spelled out, but no analysis has actually been done. Based on the hypotheses and design, the editorial board makes an accept, reject, or revise-and-resubmit decision. This ultimate accept/reject decision is made publicly, pre-registering the accepted study. It is similar to what happens these days with grant proposals and IRB reviews, but it is explicitly tied to a public publication commitment. Once the data are gathered and results processed, the paper is checked against the accepted and publicly registered hypotheses and design. So long as it conforms, it is published irrespective of the results.

Theorists would play a crucial role in the initial decision. If the study examines the effect of a policy, on what basis should we expect any meaningful effects? Are the hypotheses compelling? Will the results do much to affect our understanding of an important problem? Strong deductive reasoning and substantive familiarity with the problem are what shape our priors, and such is exactly what we need to make this call.

A steadier stream of meaningful puzzles

Popperian epistemology proposes that knowledge advances through falsification, but current pro-“significance” bias means that this happens too infrequently. We end up continuing to give credibility to theoretical propositions that empirical researchers are too afraid to falsify. We fail to offer theorists all the puzzles that they deserve. Ex ante science will provide a steadier stream of puzzles meaning more work and more fun for those who want to focus mostly on theory, and more meaningful interaction between theory and empirical research.