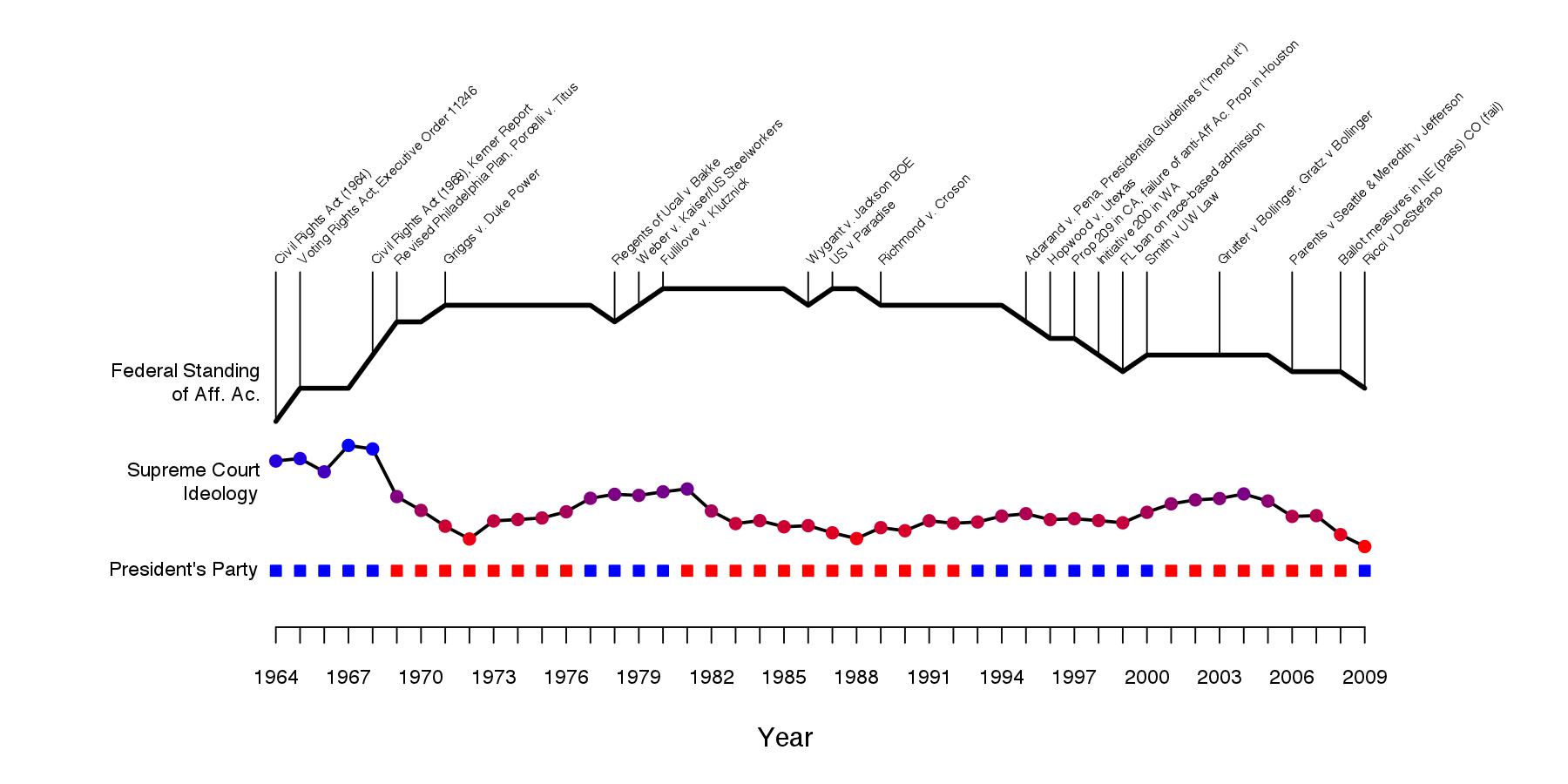

An heuristic visualization for use in my class on comparative political economy of affirmative action policies. Federal standing is scored simply by adding a point for each federal action or Supreme Court decision promoting the application of affirmative action, and subtracting a point for each action that curtails it. It is a gross simplification of course, but by appearances, it seems to capture the trends well. For example, while there have been steady curtailments since the early 1990s, it would be inaccurate to suggest federal standing is where it was at the time of enacting the Civil Rights Act in 1964. The federal level actions causing the score to increase or decrease are also shown.

Below the federal standing score is a plot of the Martin-Quinn score (link) of the median Supreme Court justice, a measure of the court’s liberal orientation (shown as blue, higher values) versus conservative orientation (red, lower values). Below that is a timeline of the party of the president.

John David Skrentny, in his magisterial account of the evolution of affirmative action politics in the US (link), highlights crisis management in the face of the race riots of the mid-1960s and US leadership’s concerns over international reputation during the Cold War as crucial determinants of affirmative action’s rise in that period. We can see that, at least by measure of party and court ideology, the institutional/ideological context was also especially receptive. At the same time, trends pushing upward the federal standing of affirmative action continued despite Nixon assuming office and a trend toward conservatism on the court.

Interesting. Very interesting. There are many complexities associated with affirmative action programs and policies. However, one issue which we continually ignore, as is the case with most government related programs and initiatives, is whether it is effective in addressing past wrongs. Think about this: How many beneficiaries of affirmative action programs have actually shared their good fortune with other members of their particular ethnic group, as opposed to using their increased opportunities and wealth to distance themselves from the masses of minority citizens?

Good question, and for answers I would point you to a review essay by Holzer and Neumark (2000; link). They find, for example, that while black medical students on average have lower test scores (suggesting that a non-negligible fraction may not have been admitted were it not for affirmative action), they do go on to graduate at normal rates and then have a much higher propensity to go on and service poor communities. To the extent that the latter is a goal, then it is a compensating benefit. Weisskopf also takes up this point in his book length comparison of affirmative action policies in the US and India (link), finding similar results in other domains, if I recall correctly.